การใช้คำอ้างถึงผู้ที่มีอัตลักษณ์หลากหลายทางเพศในสื่อภาพยนตร์ภาษาอังกฤษ: กรณีศึกษาจากซีรี่ย์ Queer as Folk ภาคที่ 1 ตอนที่ 1 ถึง 5

Main Article Content

บทคัดย่อ

งานวิจัยชิ้นนี้มีวัตถุประสงค์เพื่อศึกษาการอ้างอิงทั่วไปที่มักใช้ในการกล่าวถึงกลุ่มบุคคลที่ไม่ระบุการแบ่ง

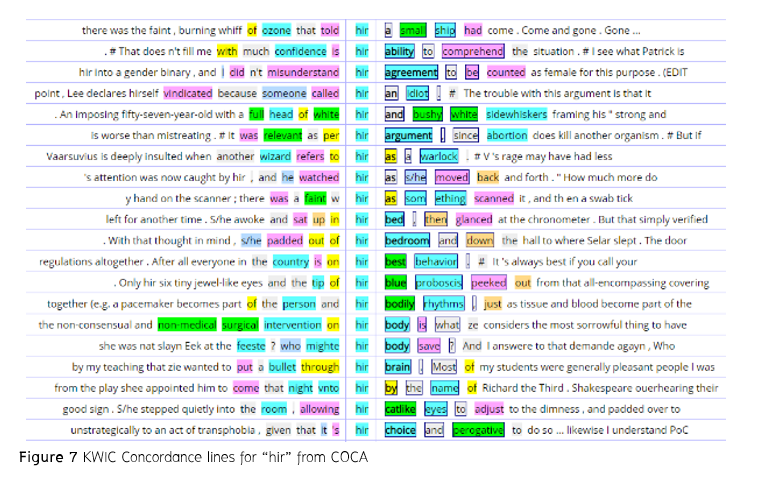

อัตลักษณ์ทางเพศ (นอน-ไบนารี่) ในสื่อภาษาอังกฤษที่ใช้ในซีรีย์ Queer as Folk ภาคที่ 1 ตอนที่ 1 ถึง 5 โดยใช้โปรแกรม AntConc เวอร์ชั่น 3.5.7. เป็นเครื่องมือหลักในการรวบรวมข้อมูล ทั้งนี้ผู้วิจัยได้รวบรวมข้อมูลและดาวน์โหลดบทพูดผ่านช่องทางออนไลน์จากซีรีย์ Queer as Folk ภาคที่ 1 ตอนที่ 1 ถึง 5 การออกแบบการวิจัยจึงอาศัยกระบวนทัศน์ทางการวิจัยเชิงปริมาณในการหาความถี่ของข้อมูลพื้นฐานของโครงสร้างข้อมูลที่นำเข้าเพื่อให้ได้ผลการวิจัย ผู้วิจัยได้ใช้หลักการทางภาษาศาสตร์คลังข้อมูลเป็นเครื่องมือวิเคราะห์ความถี่จากรายการคำศัพท์โดยใช้โปรแกรม AntConc เพื่อตีความหมายข้อมูล ผลการวิจัยพบว่าคำนามหลัก “Michael” เป็นคำที่ใช้บ่อยที่สุดซึ่งไม่ถือว่าเป็นคำที่มีความหมายทางไวยากรณ์ (Function Word) มีความถี่ที่พบจำนวน 892 ครั้ง คำว่า “he, his, him และ Emmett” มีความถี่ที่พบจำนวน 594, 477, 296 และ 282 ครั้งตามลำดับ คำที่มีความหมายทางไวยากรณ์เพียงประเภทเดียวเท่านั้นที่นำมาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของงานวิจัยนี้ได้แก่คำสรรพนามเนื่องจากเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของวัตถุประสงค์ของงานวิจัยในการสำรวจการใช้คำอ้างอิง การศึกษาในครั้งนี้ให้ผลลัพธ์ที่แตกต่างจากการศึกษาก่อนหน้านี้ซึ่งการศึกษาก่อนหน้านี้พบว่ามีการใช้คำสรรพนามที่เป็นกลางทางเพศที่พบว่าถูกใช้ เช่น Ze, Hir และคำอื่น ๆ แต่การศึกษาครั้งนี้พบว่าไม่ปรากฏการใช้คำสรรพนามที่เป็นกลางทางเพศ ทั้งนี้ผลการวิจัยสามารถสะท้อนให้เห็นถึงการใช้คำอ้างอิงหรือสรรพนามทางเพศที่สามารถใช้ในการสื่อสารกับผู้ที่มีความหลากหลายทางเพศได้

Downloads

Article Details

อนุญาตภายใต้เงื่อนไข Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

บทความที่ได้รับการตีพิมพ์เป็นลิขสิทธิ์ของบัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฎเชียงใหม่

ข้อความที่ปรากฏในบทความแต่ละเรื่องในวารสารวิชาการเล่มนี้เป็นความคิดเห็นส่วนตัวของผู้เขียนแต่ละท่านไม่เกี่ยวข้องกับมหาวิทยาลัยราชภัฎเชียงใหม่ และคณาจารย์ท่านอื่นๆ ในมหาวิทยาลัยฯ แต่อย่างใด ความรับผิดชอบองค์ประกอบทั้งหมดของบทความแต่ละเรื่องเป็นของผู้เขียนแต่ละท่าน หากมีความผิดพลาดใด ๆ ผู้เขียนแต่ละท่านจะรับผิดชอบบทความของตนเองแต่ผู้เดียว

เอกสารอ้างอิง

Anthony, L. (2000). Developing AntConc for a new generation of corpus linguists. In S. Granger, J. Hung, & S. Petch-Tyson (Eds.), Computer learner corpora, second language acquisition and foreign language teaching (pp. 3-17). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Biber, D. (1993). Representativeness in corpus design. Literacy and linguistic computing, 8(4), 223-257.

Bodén, E., & Hammer, S. (2008). Gender structure in children’s books for preschool. (Unpublished bachelor thesis, Mälardalen’s College).

Boontam, P., & Phoocharoensil, S. (2018). Effectiveness of English preposition learning through data-driven learning. 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature, 24(3), 125-141. DOI: http://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2018-2403-10

Bowker, L., & Pearson, J. (2002). Working with specialized language: A practical guide to using corpora. London: Routledge.

Brammer, R., & Ginicola, M. M. (2017). Counseling transgender clients. In M. M. Ginicola & J. M. Filmore (Eds.), Affirmative counseling with LGBTQI_ people. Virginia: American Counseling Association.

Brauer, D. (2019). Complexities of supporting transgender students’ use of self-identified first names and pronouns. Journal of College and University, 92(3), 11-12.

Darr, B., & Kibbey, T. (2016). Pronoun and thoughts on neutrality: Gender concerns in modern grammar. Journal of Undergraduate, 7(1), 73-75.

Evison, J. (2010). What are the basics of analysing a corpus? In A. O’Keeffe & M. McCarthy (Eds.), The routledge handbook of corpus linguistics. London: Routledge.

Klomkaew, S., & Kanokpermpoon, M. (2021). The use of references in English printed media to refer to LGBT people. (Master’s thesis, Thammasat University).

Klomkaew, S., & Kanokpermpoon, M. (2022). Ze is better than Hir? A corpus-based analysis in digital news and magazines. The New English Teacher, 16(1), 125-152.

Knutson, D., Koch, J. M., & Goldbach, C. (2019). Recommended terminology, pronouns, and documentation for work with transgender and non-binary populations. Practice Innovations, 4(4), 214-224. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000098

Leech, G. (1991) “The state of the art in corpus linguistics.” In Aijmer, K. & Altenberg, B. (Eds.) English corpus linguistics: Studies in honour of Jan Svartvik. London: Longman.

Lindquist, H. (2009). Corpus linguistics and the description of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

McGlashan, H. & Fitzpatrick, K. (2018). I use any pronouns, and I’m questioning everything else: Transgender youth and the issue of gender pronouns. Sex Education, 18(3), 239-252.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

O'Keeffe, A., McCarthy, M., & Carter, R. (2007). From corpus to classroom: Language use and language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Siebler, K. (2012). Transgender transitions: Sex/gender binaries in the digital age. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 16(1), 74-99. doi:10.1080/19359705.2012.632751

Sinclair, J. (1990). Collins COBUILD: English grammar. London: Collins.

Stewart, D., Renn, K. A., & Brazelton, G. B. (2015). Gender and sexual diversity in U.S. higher education: Contexts and opportunities for LGBTQ college students. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Törmä, K. (2018). Collocates of trans, transgender(s) and transsexual(s) in British Newspapers: A corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis. (Master’s thesis, Mid Sweden University).

Udry, J. R., & Campbell, B. C. (1994). Getting started on sexual behavior. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

World Health Organization. (2013). Gender. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/topics/gender/en/